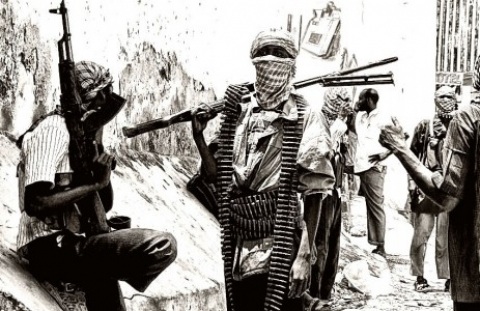

It has killed as many as 10,000 people, displaced an estimated two million others, and seems set to spread beyond the confinement of Nigeria’s borders. One would now be hard-pressed to deny that the Boko Haram insurgency is fast becoming the preeminent threat to stability both within Nigeria and among its bordering neighbors. However, despite the magnitude of the threat, a lack of independent reporting and oversight has left much information related to the insurgency rooted in suppositions and conjecture. We know little more about the extremist sect today than we did when Boko Haram made the transition from an evangelical civic movement to a fully-fledged militant group at the turn of the decade. Unfortunately, this paucity of verifiable information has blurred the analytical line between what can be considered fact and what can be considered fiction in the Boko Haram discourse — a line which I myself have crossed on occasion. In this briefing, however, I hope to redeem myself by dissecting some of the common claims being made about Boko Haram and attempt to provide some clarity to the issues at stake.

Did Boko Haram declare a caliphate?

A common misconception pertains to the sect’s purported declaration of an Islamic caliphate in northeastern Nigeria, comparable to that professed by the so-called Islamic State (ISIS). These suggestions can be linked to a video released by the sect on August 24, 2014, following its capture of the town of Gwoza. Over the course of the 52-minute video it is claimed that Boko Haram’s firebrand leader Abubakar Shekau had, in his native Hausa dialect, declared “thanks be to Allah, who gave victory to our brethren in Gwoza and made it part of the Islamic caliphate.” The English translation of Shekau’s speech, which was widely circulated by Western media, was flagged as incorrect by various sources, most notably the US government’s Open Source Center and Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, Dr. Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, who claimed Shekau had not once used the Hausa or Arabic term for caliphate, khilafah, much less declared one. It seems that confusion had arose with Shekau’s use of the word ‘Dawlah’ which denotes a state which is governed under Islamic law.

Is Boko Haram copying ISIS?

A growing number of people have suggested that Boko Haram may be copying ISIS and could even be operating as the group’s Nigerian proxy. Suggestions of synergism between Boko Haram and ISIS were ostensibly driven by the aforementioned mistranslation which suggested that Shekau had declared his own Islamic Caliphate. But even if Shekau did in fact declare the existence of a caliphate in north eastern Nigeria, this would not be tantamount to Boko Haram being linked to, or even emulating, ISIS.

From its inception, Boko Haram’s raison d’etre has been to create a state in northern Nigeria that would be governed under sharia law. As such, Boko Haram’s intention of forming a sovereign Islamist state predates even the formation of ISIS.

That said, linkages between Boko Haram and ISIS cannot be discounted entirely. In a recent briefing, Boko Haram analyst Jacob Zenn provides compelling evidence to suggest that, at the very least, Boko Haram was mimicking ISIS. Zenn argues that Boko Haram’s use of the ISIS rayat al-uqab flag and national anthem in its videos, and Shekau’s lauding of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi may be indicative of a growing relationship between the jihadist organizations. More recently, founder of the Jihadology think tank and Richard Borrow fellow, Aaron Y Zelin, also presented evidence of possible linkages between Boko Haram and ISIS. In his piece, entitled The Clairvoyant: Boko Haram’s Media and The Islamic State Connection, Zelin analyses how Boko Haram’s newly created media outlet, ‘Urwah al-Wuthqa (The Indissoluble Link), was releasing propaganda videos which mirrored those released by ISIS in terms of both production quality and methodology. Zelin also highlighted how media content released by Boko Haram’s media wing was being endorsed and disseminated by vetted ISIS social media accounts. Nonetheless, both Zenn and Zelin fall short of suggesting that linkages between ISIS and Boko Haram were definitive.

Does Boko Haram control an area the size of Belgium in Nigeria?

Another claim worth investigating is whether Boko Haram had captured a land mass in northeastern Nigeria comparable to that of several Western states.

For example, The Telegraph suggested that Boko Haram controls an estimated 52,000 square kilometers, (20,077 square miles) equivalent to the landmass of Costa Rica or Slovakia. The Guardian’s estimation of Boko Haram’s territorial appropriation is more conservative at about 20,000 sq km (7,722 sq m) – comparable to that of Wales or the US state of Maryland. The Wall Street Journal’s estimate seems to find a middle ground by suggesting that Boko Haram has assimilated an estimated 30,000 sq km (11,583 sq m) of territory, or an area equivalent to the size of Belgium. But which of these figures, if any, are correct?

I tracked the first mention of the extent of Boko Haram’s territorial expanse to an article by Nigeria’s Daily Trust. Published on November 3, 2014, it claims Boko Haram had captured 10 local government areas in Nigeria’s northeastern Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states, cumulatively amounting to 21,546 sq km (8,318 sq m) of land. By January 2015, however, it was claimed that Boko Haram captured as many as 24 local government areas in north eastern Nigeria or an estimated 30,000 sq km (11,583 sq m) of territory.

But a major problem problem with these figures, however, is that they may be rooted in a flawed conceptual definition of what can be classified as captured territory’. Eyewitness accounts have confirmed that Boko Haram does not operate as a quintessential occupying force. Many settlements claimed to have been attacked by the sect are often raided, abandoned and left to be repopulated by displaced communities. In many cases, existing governance structures uprooted in these areas are not restored. This may be creating the perception that all ungoverned spaces in north eastern Nigeria have fallen under Boko Haram rule. A claim which, like many other associated with the insurgency, may not represent the reality on the ground. In February 2014, US intelligence estimated that Boko Haram had a fighting force of around 4,000 to 6,000 fighters. A rather sparse number for a force entrusted to govern, protect and expand a land mass comparable to the size of a medium-sized European nation

Did Boko Haram kill 2,000 in Baga?

Boko Haram has been accused of committing several mass atrocities, but no claim was as stark as the one that the sect may have killed as many as 2,000 people in the city of Baga and its environs in early January of this year. But how credible is the death toll? In my column for Daily Maverick, I argued that issues such as eyewitness reliability, relative population density, and incident chronology raised serious questions regarding the veracity of the casualty numbers. A similar argument was also presented by the Africa-focused fact-checking NGO, Africa Check. Although satellite imagery acquired by Human Rights Watch supported eyewitness accounts that acts of mass violence were perpetrated in Baga, there is still little evidence to either confirm or refute the 2,000 death toll.

Is Maiduguri being surrounded?

A claim which has been circulating for a while now is that Boko Haram has captured the city of Maiduguri, the capital of Borno. Suggestions of the besiegement of Maiduguri gained further traction in January 2015 when the sect launched successive attacks on the city, both of which were repelled by Nigerian security forces. On January 25, further credence was given to these claims when Human Rights Watch Executive Director Kenneth Roth claimed that “Boko Haram had completely surrounded Maiduguri”.

Again, there were some doubts around this claim. According to local reports, Boko Haram had secured control of 13 local government areas in Nigeria’s northeastern states of Borno, Yobe, and Adamawa. Plotting these areas on a map delineates that Boko Haram had indeed taken up positions along Maiduguri’s eastern, southern and northern borders. However, it also indicated that the city’s western front, which links Maiduguri to Yobe’s capital, Damaturu, remained accessible for movements in and out of the city. In an article published in January, journalist Simon Allison suggested that four of the main roads leading to and from Maiduguri had fallen under the control of Boko Haram, but the western approach to Maiduguri remained in government hands. Whether Maiduguri was indeed being encircled is likely to become less relevant to the Boko Haram discourse, however, amid evidence that Nigerian army is successfully dislodging the sect from areas near the Borno State capital.

Is Nigeria relying on foreign forces to beat Boko Haram?

The answer to this question is “yes and no.” It is obvious that the Nigerian government has struggled to contain Boko Haram. The reason for its inadequate response is rooted in claims of chronic corruption, a lack of political will, and a reliance on an under-resourced military. But Nigeria is not solely to blame for Boko Haram’s preeminence. Evidence dating as far back as 2011 suggests that Boko Haram was in the process of establishing an operational presence outside of Nigeria’s expansive and poorly policed borders. This cross-border expansion is intrinsic in explaining both the sect’s ascendency and the failure of Nigeria’s counterterrorism strategy.

By infiltrating neighboring countries such as Cameroon, Niger and, to a lesser extent, Chad, Boko Haram not only established an operational platform from which to execute cross-border attacks, but had also garnered a safe haven, which it utilized to evade intensified counterinsurgency operations undertaken by the Nigerian government. By constantly denying that the group was operating within its borders, Nigeria’s neighbors further allowed the problem to fester. Consequently, while Nigeria is in dire need of regional assistance in its fight against Boko Haram, the actions of its neighbors should not be framed as an act of altruism. Instead, it should be presented as an admission that the Boko Haram threat is one of regional proportions and desperately requiring a regional response.

What is the meaning of the name Boko Haram?

Undoubtedly, the most common misrepresentation of Boko Haram concerns its name. The preferred name of the group among its members is Ahl al Sunna li al Da’wa wa al Jihad, loosely translated as “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad.” The origins of the appellation Boko Haram is as widely disputed as its actual meaning. According to Nigerian journalist Andrew Walker it was coined by residents of Maiduguri, who mocked the sect for its eccentric proselytization and aggressive anti-Western rhetoric – an assertion that has gained credence by the sect’s frequent rejection of the name Boko Haram.

As mentioned, the exact meaning of the term Boko Haram is also subject to contention. Although widely translated as meaning “Western education is sinful”, religious scholars and linguists continue to debate the denotation of the term. Alex Thurston, an Assistant Professor in the African Studies Program at Georgetown University, has cited the research of Hausa linguist Dr. Paul Newman that the term boko is not etymologically derived from the English term book. The researchers instead claim it is a native Hausa word, originally meaning sham, fraud or inauthenticity. Both Newton and Thurston conclude, however, that the name Boko Haram is still rooted in the sect’s belief that Western education and institutions are deceitful.

Why all the misinformation?

So why is there such a large amount of misinformation around Boko Haram? Agence-France Press West Africa Bureau Chief Phil Hazlewood offers a possible explanation, by detailing the myriad challenges media agencies face when trying to provide accurate reportage on the insurgency. Destroyed telecommunications infrastructure, a hostile government, and an even more inimical than usual subject in Boko Haram, are but a few of the obstacles journalists covering the issue encounter on a daily basis. Hazlewood’s thoughts have been echoed by BBC Nigeria correspondent Will Ross.

And by no means is this briefing aiming to trivialize the complexities outlined by Hazlewood and Ross. As mentioned, misperceptions about Boko Haram is not only limited to the field of journalism but has permeated to all disciplines discussing and theorizing on the myriad aspects of the group and its brutal insurgency. On the contrary, this briefing responds to the very problems encountered by seasoned professionals and argues that we should be more considered when digesting information related to a crisis that has become as deadly as it is misunderstood.